The Great Moon Hoax: A 19th Century Sensation

Written on

Chapter 1: The Allure of Extraterrestrial Life

Throughout history, the quest to uncover whether life exists beyond our planet has intrigued both scientists and the general public. If life could emerge on Earth, could it not also thrive elsewhere? And if extraterrestrial life does exist, might there be intelligent beings navigating the vast cosmos?

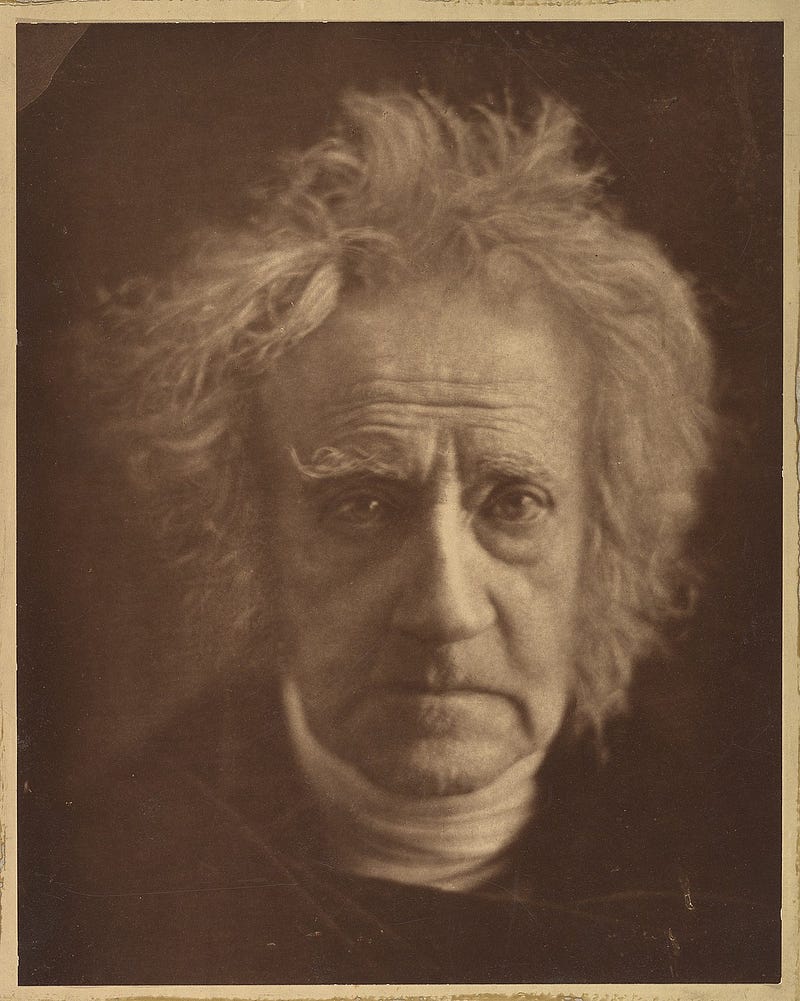

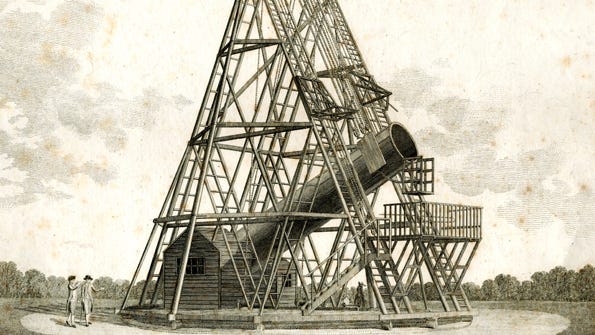

In August of 1835, The New York Sun, a prominent newspaper in New York City, released a remarkable six-part series that claimed the discovery of intelligent life on the Moon. The articles detailed the exploits of the renowned British astronomer, John Herschel, who supposedly undertook a covert mission for the British Government. He reportedly constructed a massive reflector telescope in the Cape of Good Hope, Southern Africa, adding a microscope to it as an eyepiece. Allegedly, this allowed him to magnify images up to forty-two thousand times, enabling him to observe the Moon's surface in extraordinary detail.

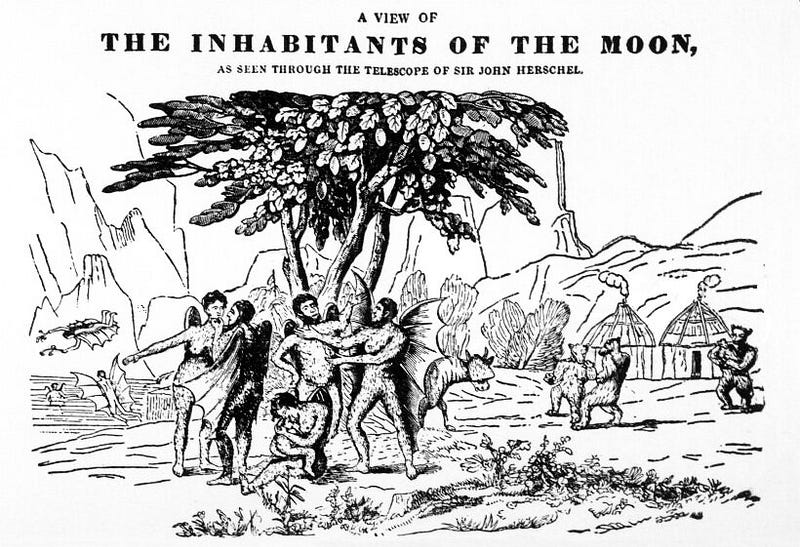

According to the reports, Herschel identified seas, rivers, forests, and valleys on the lunar surface, even claiming to witness peculiar lunar creatures, including bipedal beavers that could create and utilize fire. Moreover, he described a bizarre species of humanoid beings with bat-like wings covered in fur. For a time, these "discoveries" dominated conversations in New York and soon spread across the United States. The circulation of The New York Sun skyrocketed, with the editors scrambling to print additional editions filled with tales of these lunar "bat-people." Other publications, including the New York Times, felt compelled to join the frenzy, covering the stories of the so-called "moon people."

Various suggestions emerged regarding how to establish contact with these lunar "brothers." One proposal involved arranging stone letters on the Great Plains, so they would be visible from the Moon, eagerly awaiting a response. Some American Protestants even contemplated sending missionaries to the Moon to convert the Lunians to Christianity. This "fake news," a term we would use today, eventually crossed borders, being translated into multiple languages, including German, Spanish, French, Portuguese, Italian, Turkish, and Russian. However, it failed to elicit a similar reaction in Europe.

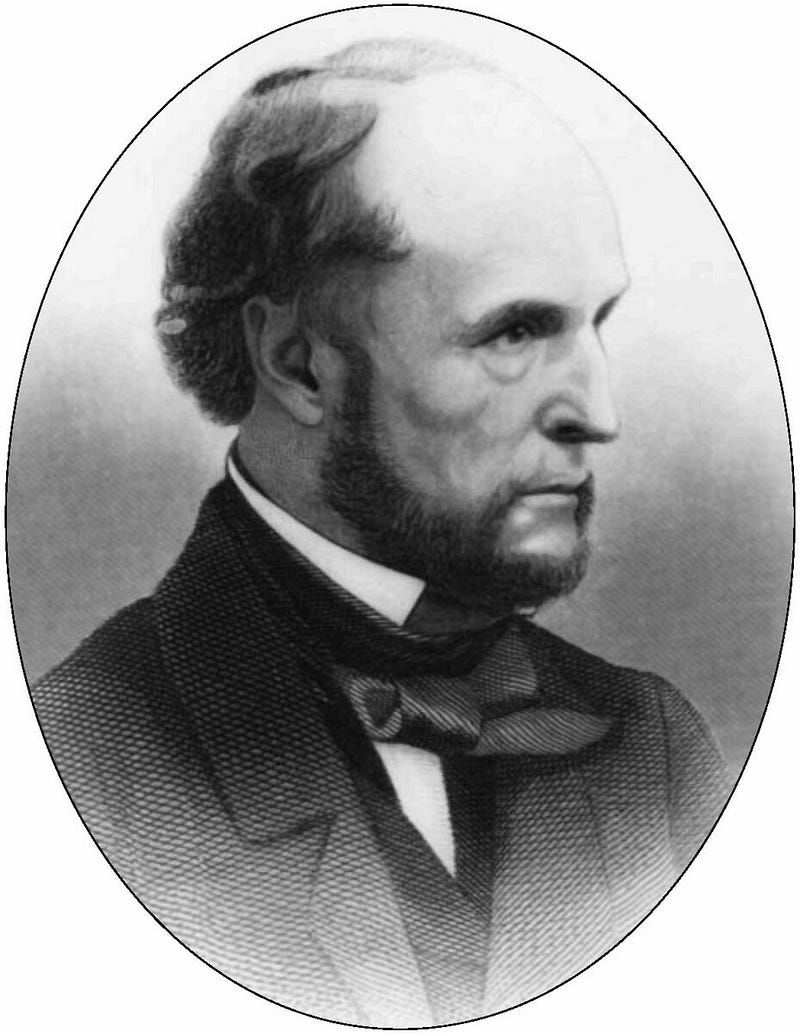

Fortunately, the hoax was quickly uncovered. The articles were penned by Richard Locke, the editor of The New York Sun, who sought to boost the newspaper's circulation during a period of low competition. While skeptics raised doubts about the authenticity of the claims, many readers initially embraced them as factual, despite the implausibility of the described telescope.

A delegation from Yale University later visited the newspaper to request access to the European scientific journals cited in Locke's articles. Unsurprisingly, no such journals existed, but Locke managed to conjure up excuses, allowing the delegation to leave empty-handed. Although Locke never publicly acknowledged authorship of the articles, it is rumored that he revealed the truth while intoxicated at a bar shortly after the publication. Competing newspapers quickly disseminated this revelation, questioning the validity of The New York Sun's claims. Surprisingly, this did not impact the newspaper's circulation.

Even after the truth came to light, some individuals continued to believe in the existence of lunar "bat-people." Ultimately, John Herschel himself put the matter to rest when he confirmed during a public lecture in New York that the entire story was fabricated. Today, one might wonder why so many people were so gullible. In the early 19th century, the notion of life on other planets, including the Moon, was not as far-fetched as it may seem now. Numerous esteemed scientists entertained the possibility of extraterrestrial life. The articles were skillfully written, filled with scientific jargon, and even included references to reputable scientific journals, such as the Edinburgh Scientific Journal.

The credibility of the claims was bolstered by the respected figure of John Herschel, whose fame rivaled that of contemporary luminaries like Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking. Furthermore, during that time, European science was highly regarded, and Herschel's actual presence in the Cape of Good Hope conducting astronomical observations lent further authenticity to the narrative.

While it's easy to mock those who believed in this absurdity, it’s essential to recognize that creators of fake news continue to employ similar tactics with remarkable success today.

Clap if you want to see more space-related articles in your feed! Subscribe to our channel and submit your questions, which I will address in future articles.

Chapter 2: The Impact of the Great Moon Hoax

The first video titled "Great Moon Hoax of 1835" dives into the fascinating historical context of the hoax, detailing its impact and the public's reaction.

The second video, "The 'Great Moon Hoax' that fooled the world – BBC REEL," provides a captivating exploration of how this story captivated audiences worldwide.